Para terminar con Nagaland, con los Konyaks Phejin se ha ofrecido a escribir un pequenio relato, sobre su abuelo, sobre sus costumbres, sobre como los cambios de este ultimo siglo han cambiado la vida tribal.

Os dejo lo que ha escrito ella, y una traduccion, que le tengo que agradecer muchisimo a mi madre ya que yo ahora no puedo escribir en Internet y ella se ha hecho cargo.

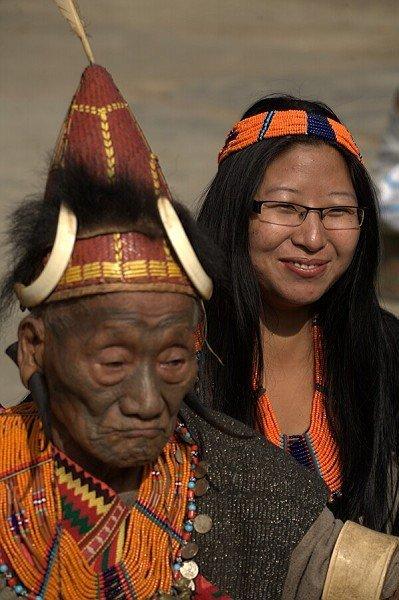

My Grandfather’s stories would always enthral me as a child,pressed snugly against his warm tattooed chest,and gazing up to his face that had distinctive tattooed marks,marks from the heydays of the practise of Headhunting and the culture of compulsory facial and body tattooing for both males/females,of the Konyak tribal way of life, way before the advent of the outsiders and christianity and conversion to it. To my curious child’s mind,listening to my Grandfather fascinated and enthralled me,and his tales were incomparable which off course didnt have Cinderella or Snowwhite and fairies,but valorous warriors and tribal damsels.

Grandpa lived for 98 years but i can say that he lived and saw way beyond that.He lived’1000 years in a lifetime” in which he saw and experienced the transition of our Konyak tribal society.He was born at a time when Headhunting and tattooe practise was active and a way of life.To the Konyaks,headhunting was carried out just as revenge in feuds against villages,or as payback for the life of a relation or kinsman. Outside people started creating and spreading fictitious stories that libelled us as even practising cannibalism and murdering any person that ventured into our territory which was totally untrue.They didnt know

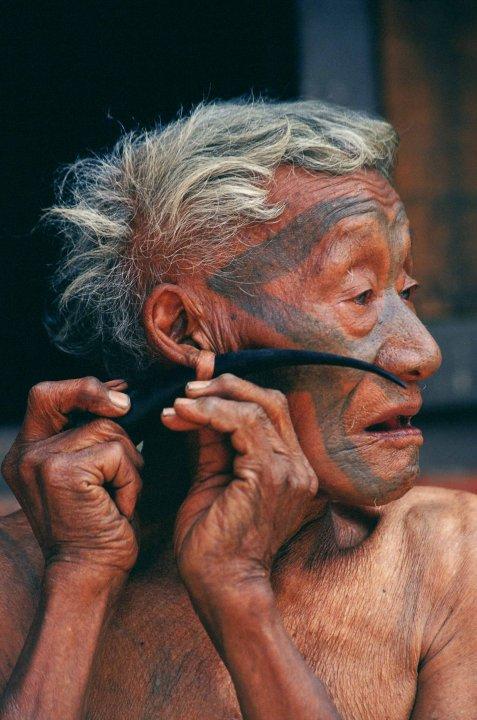

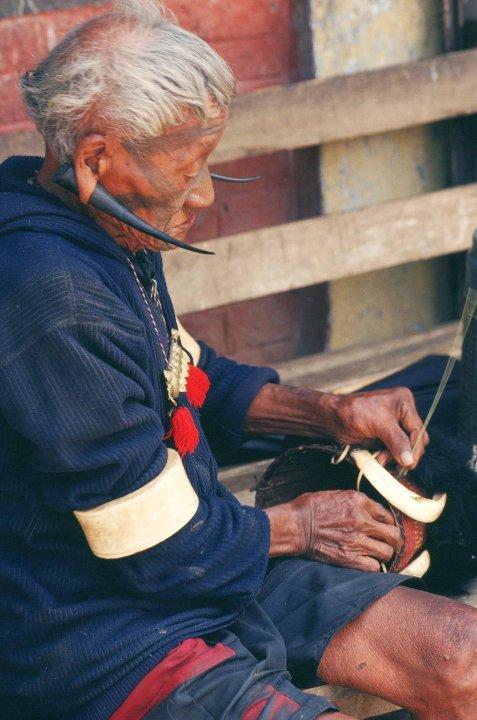

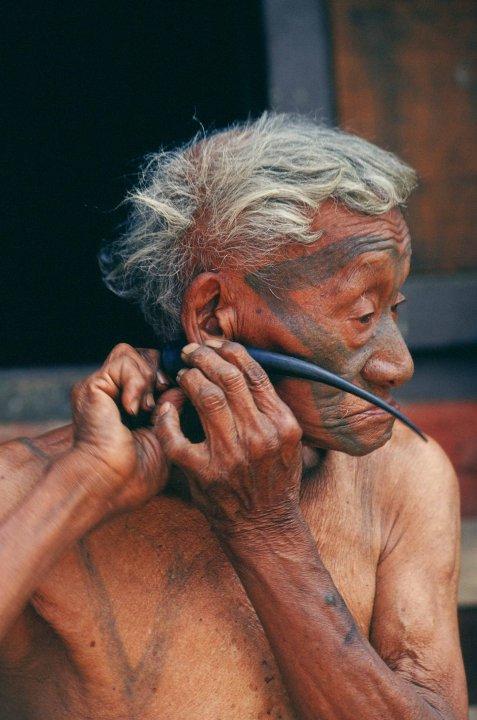

that Konyak people were hospitable and warm and lived in a free and liberal society where men and women shared equal status and liberty. The Konyaks were the last of the Naga tribes to give up headhunting which was officially outlawed by the British in 1935.They lived in villages perched on top of hills so that they could see the approach of their enemies and outsiders.They lived in’Longhouses’ made of bamboo and thatch of palmleaves,and the people were divided into clans,and marriage within the clan was strictly prohibited.But intermarriage outside one’s clan was possible.Each village had ‘Morungs’(Male dormitories),where the men gather to hold meetings and discussions.(All males had to pass through the initiation ceremony to enter or join the Morung and be a member,which was a test of manhood and valour. Likewise,all girls and boys as they attain puberty had to go through the process of tattooing,the boys on their faces and bodies and the unmarried girls on their calves,and after they marry then on their thighs as they go to their husbands house. The procedure was a torturous affliction from what my Grandfather described and would sometimes take days to complete.Sharpened spikes of hollow bamboo tubes would be dipped into a coloured solution which was a pigment from the bark of a tree and

diluted by heating on the fire,and then pricked on the skin. Outsiders ventured into the Konyak territory only around the 1920′s and 1930′s,and the first anthropological study was made by Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf,which he later wrote about on the Konyaks in- THE NAKED NAGA. Then arrived the Christian Missionaries who belonged to the other Naga tribes and who had already converted to Christianity from the arrival of the Western missionaries to their areas some 30 to 40 years earlier and were now educated.With advent of Christianity,majority of the people converted as it promised education and a better life.And so the practise of tattoo was brought to an end,as with alot of the old culture and way of life and they had to be baptised to become Christians.This led to awareness for education and the world outside. Grandpa also spoke about Barter system and exchanging of goods and trade with the people in the plains.The Konyaks who lived in the hills would bring down handicrafts,betel leaves,and other indigenous produces to the people in the plains and in exchange would get salt,tea,lime,wax,etc which gave birth to a pidgin or trade language.This brought about interaction with the outside world alongwith introduction to technologies and modern way of life.The impact was immense on the tribal way of life from the days of headhunting and tattoo culture to the present day of satellite tv and mobile phones and the age of internet. That is why,my Granfathers life was a ‘Thousand years in a lifetime’. What im today is an attribute to him.And im fortunate to have listened to him because what i’ve written and what i’ve learnt is all because of him,and i hope to be the bridge of knowledge that connects the way of his life to the people outside who read this,and to future generations of Konyaks because everything is evolving fast.

(IN LOVING MEMORY OF MR.HAMKHAO KONYAK)By Phejin Konyak.

Las historias de mi abuelo me cautivaban cuando era niña y las escuchaba acurrucada tiernamente en su pecho tatuado y mirándole las marcas de los tatuajes de su cara, marcas de cuando estaba en su apogeo ” la caza de cabezas” y los tatuajes obligatorios tanto en hombres como en mujeres. Toda esta forma de vida tribal fue antes de la llegada de los extranjeros y de la conversión al cristianismo.

Para la curiosidad de una mente infantil, escuchar a mi abuelo me encantaba y sus historias eran incomparables, por supuesto en ellas no había ni “”Cenicientas” ni “Blancanieves” pero si valientes guerreros y damas de la tribu.

Mi abuelo vivió hasta los 98 años pero yo diría que vivió y vió mucho más que eso: “vivió 1000 años de una vida” por todas las vivencias que experimentó durante los cambios de la sociedad konyak.

El nació en un tiempo en el que la “caza de cabezas” y la práctica de los tatuajes eran su forma de vida.

Para los konyaks la ” caza de cabezas” se llevaba a cabo como una venganza en enfrentamientos entre pueblos o para hacer pagar a alguien por la vida de un pariente o un ser cercano.

Las gentes de otros pueblos comenzaron a difamar y a inventar historias sobre nuestro pueblo. Decían que practicábamos el canibalismo y que asesinábamos a cualquier persona que se arriesgara a entrar en nuestro territorio, hechos totalmente falsos. No sabían que las gentes Konyak eran hospitalarios y amables y que vivían en una sociedad libre donde los hombres y las mujeres compartían el mismo status y libertad.

Los konyak fueron la última tribu d Naga que abandonaron ” la caza de cabezas” que fue prohibido por ley en 1935 por los británicos.

Vivían en pueblos situados en lo más alto de las colinas para poder ver si sus enemigos o extranjeros se acercaban.

Vivían en “Longhouses” hechas de bambú y palmeras, y las personas se dividían en clanes, el matrimonio con otra persona del clan estaba totalmente prohibido, pero el matrimonio con personas de otro clan estaba aceptado.

Cada pueblo tenía “Morungs” ( dormitorios masculinos) donde los hombres mantenían reuniones o se juntaban para sus discusiones.

Todos los hombres tenían que pasar una ceremonia de iniciación para ser miembro del Morung.

Esta ceremonia era un examen de madurez y valor. De la misma forma, todos los niños y niñas, según alcanzaban la pubertad, tenían que pasar por todo el ritual de los tatuajes, los chicos en sus caras y en sus cuerpos y las chicas solteras en sus pantorillas, y una vez casadas en sus muslos, ya cuando iban a la casa del marido.

Por lo que mi abuelo me describió el proceso era de un padecimiento muy doloroso, y podía durar días hasta que estuviera completamente finalizado.

Mojaban unas afiladas puntas, hechas de bambú, en una solución de color hecha con el pigmento de la corteza de una árbol y diluída mediante el calentamiento al fuego, después se pinchaba y dibujaba la piel.

Los extranjeros no entraron en territorio Konyak hasta alrededor de 1920 y 1930 y el primer estudio antropológico fue realizado por Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf, que después escribió sobre los Konyaks en “The Naked Naga”.

Después aparecieron los misioneros cristianos que petenecían a otras tibus Nagas, lascuales ya se habían convertido al cristianismo hacía unos 30años, cuando llegaron loas misiones de occidentey ya tenían otra educación.Con la llegada del cristianismo, la mayoría de las personas se convirtieron prque les prometían una educación y una vida mejor. Por ello la práctica de los tatuajes llegó a su fin, como también muchas cosas de la vieja cultura y de su forma de vida.., tenían que renunciar a sus creencias y ritos y ser cristianos pr el bautismo.

Esto les llevo a tomar conciencia de la eucación y del mundo exterior. Mi abuelo también me hablo del sistema Barter de intercambio de alimentos y de comercio con la gente de la planicie. Los Konyaks que vivían en las colinas llevaban artesanías, hojas de betel y otros productos indígenas a la gente de la planicie a cambio ellos cogían sal, té, lima, cera etc… todo esto dió lugar a un lenguaje comercial

Esto también tajo más comunicación con el mundo exterior y por lo tanto la introducción de nuevas tecnologías y una forma moderna de vivir.

El impacto fue tremendo en la vida de la tribu: desde los días de “los caza cabezas” y de la cultura de los tatuajes hasta el día de hoy con tv por satélite, móviles y la era de internet.Es por eso que digo que la vida de mi abuelo fue “”miles años de una vida “

Esto de hoy es un tributo para él y para todos los Konyak. Soy afortunada por poder haberle escuchado porque todo lo que he escrito y todo lo que he aprendido es gracias a él y espero que mis palabras sean el puente de conocimiento que conecte su forma de vida con la de la gente de fuera que lea esto y para las nuevas generaciones de gente Konyak porque todo está evolucionando demasiado deprisa y estas vivencias no deben perderse.

Archivado bajo:India Tagged: Konyak, Nagaland