At Harvard Business School (HBS), students use a software program to tap into a virtual Wall Street trading floor. At the Graduate School of Design (GSD), a computer-driven, robotic arm assembles walls and carves stone. At the Widener Library, digital specialists use high-resolution cameras to electronically capture everything from ancient Chinese manuscripts to Harry Houdini’s handcuffs.

Across its Schools and academic centers, Harvard is embracing cutting-edge technology that is rapidly changing the nature of scholarship, redefining research, opening doors to information, fostering collaboration, and revolutionizing classroom learning.

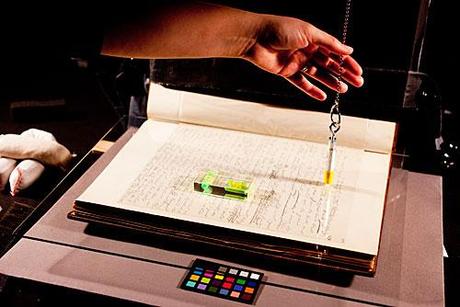

Camera Operator Edith Young scans a rare Chinese book with the help of special, high-resolution cameras. Young is one of many digital specialists across campus who are playing a major role in digitizing Harvard.

Examples abound across campus, and often involve stitching the Schools together. Recognizing the need for more digital interactivity, for instance, the Library Implementation Work Group, building on the work of the Task Force on University Libraries, two weeks ago recommended adopting a system that emphasizes a more harmonized approach to the global strategic, administrative, and business processes of the libraries.

The University’s leadership in information technology dates back more than 65 years to the Mark I, which is considered the first mainframe computer. It was the brainchild of Ph.D. physics candidate Howard H. Aiken, who envisioned a newer, faster, more powerful calculating machine.

Technology in the classroom

Aiken’s mega-computer was the prototype that paved the way for the Blackberrys and iPods of today, the powerful handheld digital devices that are ubiquitous in Harvard’s classrooms. In those classes, the fans and adopters of such technology say, electronic devices aren’t driving education, but instead are supplementing the pedagogy.

Eric Mazur, the Balkanski Professor of Physics and Applied Physics, has used wireless technology in his introductory physics class for 17 years. His students use clickers, their own handheld devices, or their computers to send answers to a common website that registers the responses on a screen in the front of the classroom. Mazur introduced the clickers to ask questions of students, to get them to discuss their answers in small groups, and to have them try to convince each other of their own reasoning.

“In the end,” said Mazur, “learning and research is a social experience. It’s people, it’s not sitting in front of a book, or sitting in front of a terminal.”

Harvard professors increasingly engage their students electronically by using clickers, virtual office hours, videos and transcripts of their lectures online, and comprehensive course websites.

In the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), Katie Vale, director of the Academic Technology Group, and her team help instructors to enhance their curricula through technology. Together, they have created a virtual model of Harvard Yard in the 17th century and a three-dimensional visualization of a virus and its reaction to certain drugs.

“What we want to be able to do is make sure the teaching is driving the technology,” said Vale. “We want to be able to solve educational problems through the use of technology and encourage faculty to try new and different pedagogical methods, such as using clickers for active learning.”

In the HBS course “Dynamic Markets,” students emulate the New York Stock Exchange through their computers. Joshua Coval, Robert G. Kirby Professor of Business Administration, and Erik Stafford, John A. Paulson Professor of Business Administration, developed a software program that simulates the financial markets. The program allows students to trade with each other, compete for opportunities, and learn the principles of finance.

“It’s a very powerful learning vehicle,” said Coval. “When it clicks, it gets imprinted in their psyche. The hope is that it will remain with them for many, many years.”

Martin Bechthold is a professor of architectural technology and director of the GSD’s Fabrication Lab, which is home to such digital devices as a computer numerically controlled, six-axis, robotic manipulator. Attached to a high-pressure water jet, the electronic arm blasts a mixture of water and garnet dust at, for example, a piece of marble to slowly carve it.

“Robotic fabrication of architectural components is, I think, one of the most exciting activities here with regard to the innovative use of technology,” Bechthold said.

Elsewhere, Harvard’s Initiative for Innovative Computing, an interfaculty effort, has developed ongoing projects that include the Scientists’ Discovery Room Lab. Part of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), under the direction of Chia Shen, the lab focuses on human-computer interaction. One promising project involves tabletop touch-screen technology that aids occupational therapy for children with cerebral palsy.

Efthimios Kaxiras, the John Hasbrouck Van Vleck Professor of Pure and Applied Physics at SEAS, and a team of collaborators have developed computer-generated simulations to model blood flow in the human cardiovascular system, work that may help to understand diseases.

In another example, involving a group of physicists half a world away at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, Alán Aspuru-Guzik, assistant professor in Harvard’s Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, has used a quantum computer to determine the energy of a hydrogen molecule.

The Berkman Center for Internet & Society, which created an early prototype podcast, is at the center of much of the University’s web research, exploring, analyzing, and enhancing cyberspace. And the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s (HGSE) Technology, Innovation, and Education program “prepares students to contribute to the thoughtful design, implementation, and assessment of media and technology initiatives.”

Harvard’s Center for Geographic Analysis buttresses University research projects with geographical information systems that use a combination of cartography, statistical analysis, and database technology. “When we try to bring time and space together, we start to be able to look at change taking place over time in many places at once, and that’s only possible with computation,” said Peter Bol, the center’s director and the Charles H. Carswell Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

Spread of distance learning

Thanks to technology, this year students at the 101-year-old Harvard Extension School can access 150 courses through its distance-learning program. Of those, 37 are Harvard College courses, and three are HGSE courses, all taught by Harvard faculty.

Students watch streaming videos of lectures and remotely interact with classmates and professors through real-time, virtual “chat” discussion boards, as well as through web-conferencing software and video conferencing. In smaller classes, students can dial an 800 number to take part in class discussions.

“By opening up its teaching expertise to a global audience, we are demonstrating how Harvard can contribute to the public good,” said Henry Leitner, associate dean for information technology and chief technology officer at the Harvard Division of Continuing Education. “It enables busy Harvard faculty, whose scarcest resource is time, to make their first-rate teaching accessible to a wider audience.”

Stanley Hoffmann, the Paul and Catherine Buttenwieser University Professor, several years ago agreed to open a class that he co-taught on U.S.-European relations on the condition that it be available to students in the Extension School and at the Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris, a prestigious French university.

“It was very instructive and enlightening for Harvard College undergraduates to learn firsthand the opinions of peer students in another part of the world.

Instead of engaging with an on-campus classmate from, say, Paris, Texas, they could discuss ideas with someone from Paris, France,” said Leitner. “It worked magnificently.”

Hunting for new online tools

John Palfrey, the Henry N. Ess III Professor of Law and vice dean for Library and Information Resources at Harvard Law School (HLS), has spearheaded an initiative to create a “library of the future” that uses technology to help the stacks “come alive in a virtual environment.”

HLS lab initiatives include Library Hose, a Twitter feed of what’s being acquired by Harvard’s libraries; Shelflife, a web application that researchers can use to access and comment on work, using common social network features; and StackView, a visual rendering of the library shelves.

Palfrey also is faculty co-director of the Berkman Center, which in 2003 created a free blogging platform for the University that now hosts more than 700 blogs. The blogs are critical, said Palfrey, because they offer scholars an important way to exchange information, allowing researchers to engage, solicit feedback, refine arguments, and “improve the quality of their work.”

Blogs can also reveal important social and cultural undercurrents, as in the center’s ongoing project evaluating the blogosphere in restrictive societies such as Iran and Russia. With these projects, “We can gauge what the reaction is to the state — what the state is blocking, who is starting these important conversations, and who is setting the agenda,” said Palfrey.

Sharing the University’s collections

Using digital tools, the University is widening access to the massive collections in its museums, libraries, and archives, providing connections to ancient documents and prized holdings for anyone with access to a computer.

At the Harvard College Library, which consists of 11 allied libraries, items that have priority for digitizing include those that are at risk of deteriorating, that are unique, that are used often, or that are likely to fit well into existing class curricula.

A five-year collaboration with the National Library of China is digitizing the Harvard-Yenching Library’s vast collection of rare Chinese books. Another of its many projects involves digitizing more than 5,000 scarce 19th century Latin American pamphlets containing political and social commentary.

“It’s a benefit to Harvard, but much more broadly to the world at large,” said Rebecca Graham, associate librarian of Harvard College for preservation, digitization, and administrative services. “It promotes scholarship not only for the researcher and scholar, but also for those who are simply curious about a particular topic.”

Through the Open Collections Program, Harvard’s libraries, archives, and museums have created six online collections that support teaching and learning anywhere. The collections bring more than 2.3 million digitized pages — including more than 225,000 manuscripts — to the web.

In addition, virtual visitors to the Harvard Art Museums can browse through images from its vast collections by tapping into its extensive online archives.

Harvard also has a key role in creating the Encyclopedia of Life, a one-stop information shop spotlighting the 1.8 million known living creatures on Earth, in collaboration with five partner institutions. The project is creating web pages with multimedia information, when available.

A collaboration between the Museum of Comparative Zoology and College of the Holy Cross biologist Leon Claessens is creating an online database, Aves 3D, that shows the museum’s 12,000 bird skeletons, including 3-D digital models of each species.

In addition, the Harvard University Archive is processing and digitizing 17th and 18th century holdings about Harvard in a program that carries special relevance. The documents, including papers and manuscripts from the School’s earliest presidents, shed light on the origins of the institution, and also on the country as it was struggling to come into its own.

“In this collection,” said University Archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, “you see these parallels between the activities and the intellectual life and the public discourse here and in the emerging country at large, and the role that Harvard played in that evolution.”

The ambitious Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard project, under the direction of Stuart Shieber, provides an open-access repository for the work of University academics.

“We want to take things into our own hands and make sure people can read the things that we write,” said Shieber, the James O. Welch Jr. and Virginia B. Welch Professor of Computer Science, who heads the Office for Scholarly Communication, which spearheads campuswide initiatives to open, share, and preserve scholarship.

The program, created two years ago following FAS passage of an open-access policy, has put more than 4,000 articles online. Active for just over a year, the site has recorded hundreds of thousands of downloads.

Keeping the information highway open

What keeps Harvard’s digital engines running is a massive underlying structure that many users simply take for granted.

“There’s a critically important infrastructure that goes along with digital Harvard that people do not see,” said Anne Margulies, Harvard’s new chief information officer.

Harvard’s web system is one of the largest and most sophisticated private networks in the country. The fiber-optic backbone of the University links close to 500 of Harvard’s buildings on campus as well as the affiliated hospitals and other medical facilities. There are thousands of servers, tens of thousands of desktop computers, and uncounted mobile devices in the digital grid.

Tasked with maintaining what is underneath the computer platform, Margulies is also helping to develop Harvard’s digital future. One aspect has already risen to the top: video.

“Currently, 40 percent of traffic on our network is video. Some predict it will be 80 in a few short years,” said Margulies, who hopes to expand the network’s bandwidth to keep pace with the rising demand for video conferencing in classrooms and streaming of courses online. “We are seeing this explosion in the demand for video, and we need to make sure that our infrastructure is able to keep up with that and support it.”

Margulies relies on support from the Harvard Academic Computing Committee, a faculty and senior administration committee that explores academic information technology issues, principles, and policies for the University.

One technology effort under way is the collaborative group known as iCommons. The Provost’s Office created the initiative in 2001 after a number of deans expressed a desire for more cooperation in online learning among the Schools. Paul Bergen, director of Harvard’s iCommons, said the group offers a suite of online resources for teaching and learning. It includes iSites, an easy-to-use web publishing and collaboration system used by about 90 percent of courses at the University.

The humanities embrace digital

Digital scholarship in the humanities is a young but robust and expanding field. Authorities say that, while past research in the humanities was largely focused on qualitative methods of inquiry, digital media and web-based technologies are being brought into the mix more often.

“There is an increasing importance of visualization in humanities scholarship, and of geospatial components like mapping and other means of organizing knowledge, rather than in narrative form,” said Jeffrey Schnapp, visiting professor of Romance languages and literatures, visiting professor of architecture, and a fellow at the Berkman Center. At Harvard, Schnapp is collaborating with the libraries and museums to explore ways to animate their archives.

For the past three years, the Digital Humanities program has worked to raise awareness of the Harvard groups that offer digital services and support. As part of that effort, the program organizes a yearly fair in collaboration with Harvard’s social science division.

At the event, Elaheh Kheirandish, a fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, presented a Micromapping Early Science project that offered a nuanced look at the development of science in Islamic lands through interactive maps that chart the transmission of scientific works and concepts.

“I am interested in the ways technology can drive the research,” said Kheirandish, a science historian. “Ideally, my hope is that this work generates research questions we would not have thought of without this technology.”

This article was published by the Harvard Gazette