Hoy tenemos la inmesa suerte de poder acercaros a estas páginas a una de esas leyendas del videojuego cuya mera presencia eclipsa cualquier tipo de palabra escrita que ose intentar acercarse a la altura del protagonista. Uno de esos currantes incansables, con tal bagaje en la industria del ocio electrónico, que sería complicado imaginarse esta sin su presencia. Sin más dilaciones: David Perry.

Hoy tenemos la inmesa suerte de poder acercaros a estas páginas a una de esas leyendas del videojuego cuya mera presencia eclipsa cualquier tipo de palabra escrita que ose intentar acercarse a la altura del protagonista. Uno de esos currantes incansables, con tal bagaje en la industria del ocio electrónico, que sería complicado imaginarse esta sin su presencia. Sin más dilaciones: David Perry. Antes de nada, queremos darle las gracias por dedicarnos parte de su escaso tiempo. Empecemos por el principio: ¿Cuándo empezó tu interés por la tecnología? ¿Cuál fue la primera máquina que tuviste?

Mi interés empezó en la escuela a comienzo de los años ochenta, pero mis profesores no me dejaban entrar al aula de informática, porque decían que yo era demasiado joven. Cuando tuve edad suficiente, me dejaron jugar con un ZX81; esa es la primera máquina. Mi madre me compró una usada a una niña de la escuela que ya no la quería más. ¡De repente podía jugar y hacer juegos en casa!

Un clásico de clásicos. Fuente: Wikipedia

Todos recordamos el profundo impacto que causaron en nuestras retinas esos primeros juegos. Estoy hablando, por supuesto, de aquellas máquinas enormes con luces brillantes y sonidos electrónicos llamadas máquinas recreativas. ¿Cuáles eran tus juegos favoritos de niño?

Al primer juego que jugué fue Pong, que un amigo mío tenía para su televisión. Había un salón recreativo cerca de mi escuela dónde tenían Pac-Man y Bump'n'Jump. La universidad que había donde nosotros tenía Donkey Kong 2, Missile Command y Phoenix. El aeropuerto de Belfast tenía la versión cockpit de la recreativa de Star Wars y Dragon's Lair. ¡En total era un buen conjuto de máquinas a las que jugar! Probablemente la que se me daba mejor era Phoenix. Siempre me han encantado los shooters verticales, siendo otro favorito mio Moon Cresta.

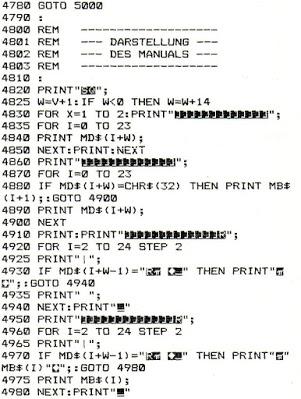

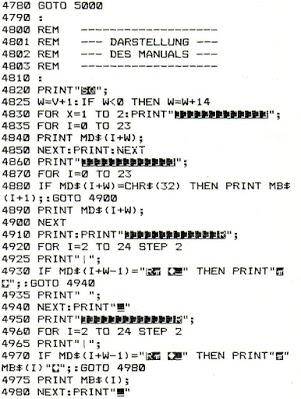

Trozo de código BASIC. Fuente: Wikipedia

En algún momento decides dar el salto al otro lado y no solo disfrutar del juego sino ponerte a hacer tus propias creaciones. ¿Qué te motivó a dar ese paso?

A principios de los años ochenta eran muy populares las revistas, y había un montón de ellas dedicadas a los videojuegos. Podías desplegar tu revista, teclear el código del juego listado en ella y jugar a nuevos juegos en cualquier momento. ¡Tanto teclear te hacía aprender a hacerlo rápido! También te enseñaba como programar juegos. "LET LIVES=3" es fácil de entender y trampear!

Así que empecé a modificar juegos hasta que pude hacer los míos propios.

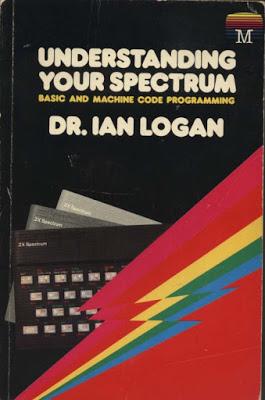

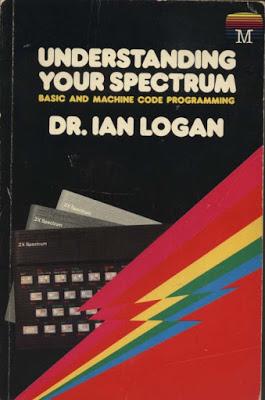

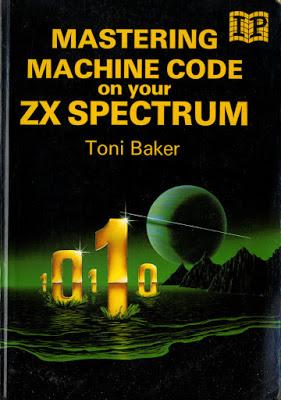

La fuente del saber

¿Cuán fácil resultaba acceder a recursos sobre programación? Allá en los ochenta se podría decir que el acceso a Internet era bastante complicado *risas*. ¿Dónde encontrabas esos recursos? ¿Cuáles eran tus favoritos?

Lo más importante era conseguir libros de programación. Había un tal Ian Logan (al cual nunca conocí) que escribió libros increíbles. Otro era Toni Baker. ¡Me ayudaron TANTO! ¡Habría pagado diez veces más por esos libros! Todavía los tengo.

Parte importante en sus inicios

¿Cuán importante fue para tu futura carrera este acceso temprano a recursos de programación? Es decir, has pasado la mayor parte de tu vida haciendo juegos, así que podemos asumir que te causaron un gran impacto. Pero, ¿qué has aprendido en estos primeros días que haya sido útil más adelante? ¿Algún truco de programación interesante que te ahorró tiempo más adelante en máquinas más potentes?

En cierto momento decidí escribir un programa que calcularía cuan rápido podría ejecutarse otro programa. Me parecía una buena idea, ya que podría hacer que mi código fuese más rápido. Lo que fue interesante es que me hizo observar a cada una de las instrucciones y pensar en la velocidad, y podría experimentar con código hasta que encontrase la manera más rápida de hacer alguna tarea. Recuerdo experimentar con código que se automodifica, dónde el código se reprogramaba a si mismo mientras se ejecutaba. ¡Era divertido!

El verdadero comienzo profesional de una carrera

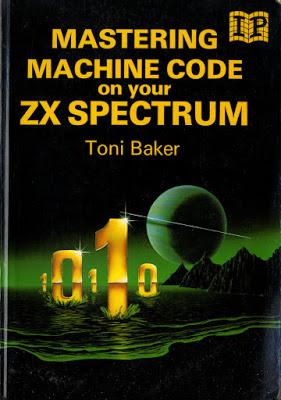

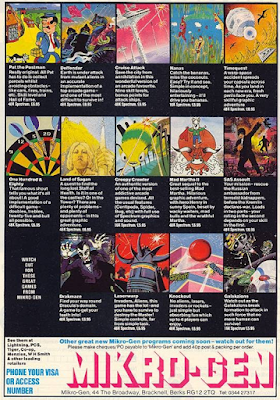

Empezaste muy temprano tu carrera publicando listados en revistas para los ZX80/81, tras lo que diste el salto a la nueva, brillante máquina, el ZX Spectrum. Con él, alcanzaste tus primeros hitos trabajando con Mikro-Gen, dónde te publicaron títulos como Three Weeks in Paradise. Pero, en algún momento, descubriste ese gran competidor a la máquina de Sinclair llamado Amstrad CPC. ¿Qué te pareció la máquina cuando oyes de ella por primera vez? ¿Qué te llevó a aprender a programarla?

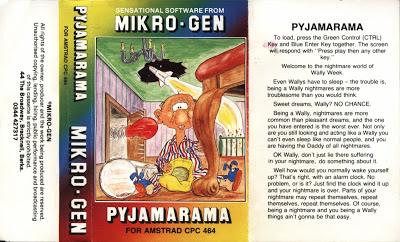

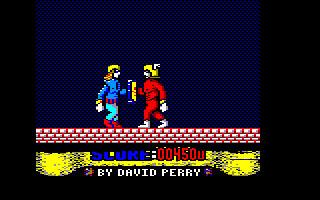

El primer juego profesional en el que trabajé fue probablemente Pyjamarama. Lo escribió Chris Hinsley para Spectrum y necesitábamos una versión para Amstrad CPC, así que hice esa conversión y me valió mi primera review de 10/10. Me encantó el Amstrad e hice más juegos para dicha máquina, pero también trabajé para Spectrum y Commodore 64. ¡Supongo que quería aprendérmelas todas!

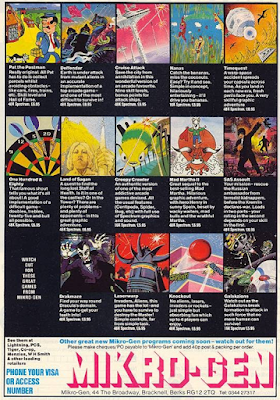

Anuncio de Pyjamarama

¿Te resultó difícil adaptarte a la nueva máquina? Sabemos que tanto Spectrum como el CPC tiene algunos componentes comunes pero, por ejemplo, la manera de trabajar del vídeo es diferente, siendo realmente fácil hacer un trabajo de mierda si trabajas en el Amstrad de la misma manera que en el Spectrum. ¿Qué ventajas le veías al Amstrad CPC? ¿Cuales crees que son, en tu opinión, sus puntos fuertes?

Amstrad era diferente a Spectrum pero, al menos, la base de la programación era la misma. Me ví quedándome sin memoria, así que escondí cosas de la pantalla que no estaban mostrándose en el monitor. Muchos y muchos trucos para lograr hacer todo lo necesario. Lo que era divertido es que no teníamos un kit de desarrollo, así que entre todos logramos encontrar una manera de descargar datos a través del puerto del joystick. ¡Funcionó!

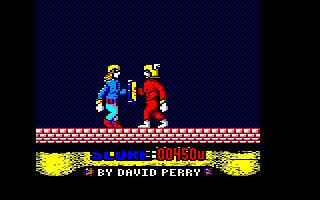

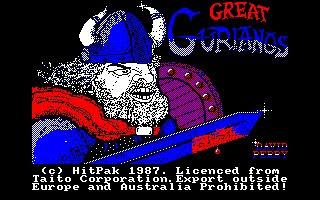

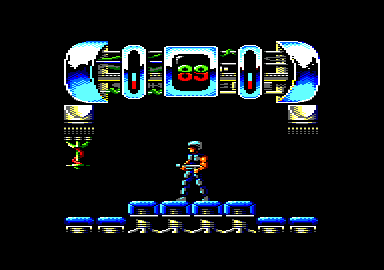

Versión de Amstrad de Great Gurianos

En Internet hay algo de información contradictoria que nos gustaría aclarar. ¿Qué nos puedes contar sobre tus primeros trabajos en la máquina? ¿Qué juegos programaste para Amstrad CPC antes de Great Gurianos?

Pyjamarama fue mi primer juego para Amstrad CPC. Great Gurianos ocurrió cuando abandoné Mikro-Gen y pensé en fundar mi propia empresa. Elite me ofreció convertir el juego y me enviaron una recreativa que para cuando llegó, yo ya había acabado el juego.

Terminado antes de recibir la recreativa

Si me permites la pregunta: ¿En que juegos para Amstrad CPC trabajaste mientras estabas en Mikro-Gen?

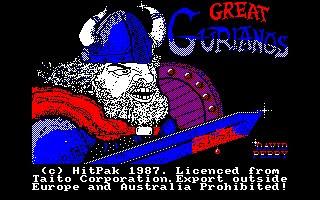

Creo que hice Pyjamarama, Stainless Steel, Herbert's Dummy Run y Three Weeks in Paradise. ¡Hace mucho tiempo de eso!

Versión de CPC de Stainless Steel

Hablando de juegos anteriores a Great Gurianos, se dice por ahí que empezaste a trabajar en la conversión de Ikari Warriors, que la terminaste pero nunca se publicó, siendo en su lugar publicada una versión hecha por David Shea. ¿Qué nos puedes contar sobre este proyecto? El juego siempre aparece en las listas de mejores juegos para Amstrad CPC de todos los tiempos, pero viendo tus otros trabajos uno no puede dejar de preguntarse si tu no habrías sido capaz de hacer una versión aun mejor...

David Shea era una autentica estrella, buen amigo y soy un gran fan suyo. Empecé a trabajar en Ikari Warriors pero, honestamente, él era mejor artista/programador y en esos tiempos solíamos trabajar nosotros mismos también en los gráficos. Estoy convencido que su Ikari Warriors sería mejor que el mío.

El comienzo de un equipo de leyenda

Tanto Ikari Warriors como Great Gurianos fueron publicados por Elite Systems, compañía que también publicó Beyond the Ice Palace. ¿Cómo fue trabajar par una compañía como Elite?

Beyond the Ice Palace se desarrolló coincidiendo con mi decisión de formar mi primer equipo propio. Dividimos el trabajo e hicimos el juego para varias plataformas. No fue tan fácil como suena, ya que estábamos acostumbrados a trabajar solos.

Sprites enormes y coloridos

Tras Elite empiezas a trabajar con Probe Software y creas dos títulos similares, con sprites enormes y un montón de partículas moviendose simultáneamente en pantalla. Hablamos, por supuesto, de Trantor The Last Stormtrooper y Savage. ¿Qué recuerdos tienes del proceso creativo de ambos juegos? ¿Algunas anécdotas divertidas?

Visité Probe Software y me encontré allí a Fergus McGovern. Me presentó a Nick Bruty, quien estaba creando Trantor para el Spectrum. Me preguntaron si podía hacer la versión de Amstrad CPC, así que la hice en casa. Con el tiempo, Nick y yo decidimos trabajar juntos como equipo, uno programando, otro como artista, y fue un encuentro divino que nos ayudo a ambos en nuestras carreras profesionales.

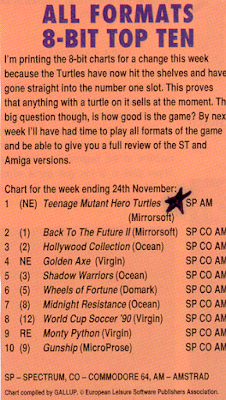

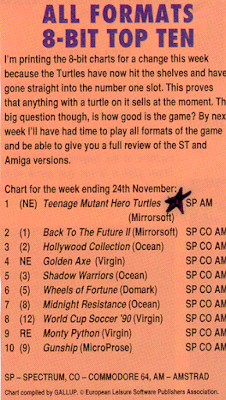

Otro número 1 a la buchaca

Es increible lo suave que se mueven ambos juegos en una máquina como el Amstrad CPC, "famosa" por sus habilidades gráficas referentes al scroll, sprites gigantes y montones de elementos en pantalla. ¡Tienes muy buena reputación como programador de Spectrum, pero esta debería ser aún mayor como programador de CPC! ¿Cómo lograste aquello? ¿Qué trucos de programación empleaste?

El CPC me importaba en serio; fue la máquina de mis primeros juegos profesionales y había juegos en dicha máquina que me obligaban a trabajar más duro, como Sorcery.

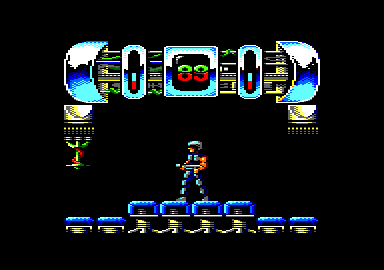

Versión de CPC de Dan Dare III

Con Dan Dare III y Teenage Hero Ninja Turtles lograste lo que yo llamo un "juego David Perry". Es decir, juegos con un scroll multidireccional realmente suave, quizás un tamaño de pantalla algo más pequeño y un montón de explosiones y elementos simultáneos en pantalla. ¿Qué nos puedes contar de estos trabajos? ¿Cuales fueron los mayores retos que encontraste y como los solventaste? ¿Cómo fuiste capaz de lograr un scroll tan suave aun teniendo un montón de explosiones en pantalla?

Tras haber hecho un montón de juegos, Nick y yo nos empezamos a preguntar que podríamos hacer para explotar al máximo los límites de la máquina. Ahí fue cuando me volví loco, como por ejemplo meter tres juegos en uno (Savage) o un juego para Spectrum llamado Extreme que hasta usaba dibujos vectoriales para darle al jugador piernas robóticas. Empezamos a experimentar con todo: 3D, montones de parallax, etc. Simplemente, amábamos lo que estábamos haciendo. No se sentía trabajo para nada.

Hicimos un juego llamado Crazy Jet Racer y Virgin quería cambiarle el nombre a Dan Dare III. Fue un buen movimiento y en realidad me he fijado en que mi carrera se movía más rápido cuando trabajaba con licencias. ¿Qué comprarías? ¿Jumpy Man o Mario? La marca importa.

Tendrás que llegar al final para ver las piernas vectoriales

1991 fue el último año en el que trabajas en nuestra máquina querida, habiendo ya empezado el Amstrad CPC a desaparecer en favor de otras máquinas mejores y más potentes. A pesar de ello, fue un año muy productivo en tu carrera, con otros "juegos David Perry" como Extreme o Capitán Planeta, además de Paperboy 2 y Smash TV. El mercado había cambiado un montón desde el inicio de tu carrera. ¿Qué recuerdas de estos tiempos inciertos?

Probe Software necesitaba juegos, juegos y más juegos... Hacíamos todo lo posible para mantener la demanda. Apenas recuerdo trabajar en Capitán Planeta, está todo difuso. Paperboy 2 fue interesante, ya que tuve que buscar una manera de generar los mapas usando código ya que no había suficiente memoria para almacenarlos a la antigua usanza. Smash TV fue divertido, pero casi me mato intentando cargar con la máquina recreativa por un tramo de escaleras. No lo hagas, podría estar muerto. Aplastado en las escaleras por Smash TV.

Versión de Amstrad CPC de Extreme

¿Habías empezado ya a reciclarte mientras trabajabas en esos juegos? ¿Aprendiste algo en el proceso de reciclaje que te fuera útil para esos últimos desarrollos de 8 bits o fue al contrario? ¿Qué trucos de programación aprendiste durante tu carrera en los 8 bits que te fueran tan útiles que seguiste empleándolos sin importar en qué máquina estuvieras trabajando?

El truco consistía en mantener una mente abierto. La gente te diría que puedes y que no puedes hacer. «Estos comandos del procesador no están documentados. ¡¡¡No puedes usarlos!!!». Lo hice. ¡Todo el tiempo! Tuve también grandes amigos como Zareh Johannes. Recuerdo estar una vez trabajando en un trozo de código para Amiga, intentando hacer scroll suavemente a 60 frames por segundo. ¡Petardeaba! Él miró por encima de mi hombro y apuntó al problema. Me acuerdo que pensé «¿cómo cojones ha podido entender mi código tan rápido?». Así que también he tenido mucha suerte por tener gente así en mi vida. Ellos te inspiran a aprender más y ser mejor en lo que haces.

Pues mola un montón la imagen para Drak-Maze

¿Es programar un arte que depende de la inspiración una vez tienes una base o es más parecido a un deporte en el que con entrenamiento puedas lograr algo?

Si amas algo, no es trabajo. Si te lo estás pasando bien, el tiempo vuela. Suelo decir que programar es como resolver puzzles. Es exactamente igual de emocionante cuando consigues algo que funciona. Es la práctica lo que importa. Tienes que invertir miles de horas; entonces el lenguaje se vuelve natural, puedes literalmente pensar en código. La gente piensa que programar es aburrido, pero no lo es para nada. Hay un momento clave en el que te das cuenta que puedes construir cualquier cosa que puedas imaginar. Mola un montón.

Publicidad de Mikro-gen

¿Hay más juegos de 8 bits de David Perry que nunca hayan visto la luz más allá de Ikari Warriors? ¿Conservas aún tus discos de desarrollo?

He empleado bastante tiempo buscando muchos de mis juegos más viejos, que solo aparecieron en revistas o libros. Alguien los ha tecleado, así que pude recuperar el código. Los juegos están escritos en BASIC, como por ejemplo Drak-Maze.

¡Aquí tenéis un juego de 1983 escrito en BASIC para una revista!

https://spectrumcomputing.co.uk/playonline.php?eml=1&downid=76613&__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=pmd_c3b51544ae81cb3ea63f67b9f133a5c2d0a305ab-1627796176-0-gqNtZGzNAjijcnBszQiO

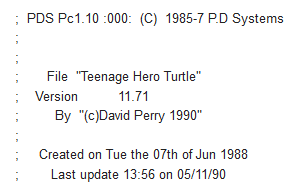

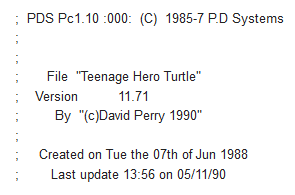

Cabecera del proyecto Teenage Hero Ninja Turtles

¿Qué herramientas usabas en tus producciones para Amstrad CPC? ¿Tenías suficiente con software comercial de la época o preferías desarrollar tus propias herramientas?

Ojalá tuviéramos aún aquel original sistema de transmitir datos al CPC por el puerto de joystick. Lo que es interesante es que mi plataforma de desarrollo fue un Amstrad PCW8512 (no tenía un PC). Lo usé para hacer juegos como Great Gurianos.

Al final de la vida comercial usaba un PDS.

https://retro-hardware.com/2019/05/29/programmers-development-system-pds-by-andy-glaister/

¡Número 1!

Hemos hablado sobre programación y desarrollo, pero ¿qué hay del proceso creativo de diseñar un juego? ¿Preferías desarrollar tus propias ideas o era más fácil trabajar en conversiones a Z80 de juegos de otros desarrolladores? ¿Cómo era ese proceso desde que tenías una idea hasta que llegabas a un proyecto finalizado?

Cuando hice Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles con Nick Bruty, fue directo al número 1 en las listas de ventas. ¡De nuevo quedó claro que licenciar franquicias es una buena idea! Cuando logras un número 1 es más fácil conseguir más trabajo :)

¡Pyjamarama!

¿Qué ha significado el Amstrad CPC en tu carrera? ¿Te ayudó a lograr tu estatus actual? ¿Cuán grande es su lugar en tu corazón?

Era un producto increíble para su tiempo. Aun no puedo creer que viniera con un monitor y con un teclado completo de alta calidad. Fue una parte muy importante de mi carrera y mi único remordimiento es que nunca conocí a Alan Sugar. Sí que conocí a sir Clive Sinclair, lo cual fue divertido.

También compré un Spectrum Next y estoy deseando jugar con él.

Otra salvajada para Amstrad CPC: Savage

¿Estás al día con las nuevas producciones para Amstrad CPC? ¿Cuales son tus títulos favoritos de los últimos años?

Ya que ahora vivo en los Estados Unidos, por desgracia no encuentro mucha gente que conozca al CPC. ¿Qué juegos me recomendarías que le echara un vistazo? ¡Tengo un emulador de CPC en una Raspberry Pi y así es como vive la máquina para siempre! Soy un gran fan de la emulación ya que está preservando la historia de esta industria.

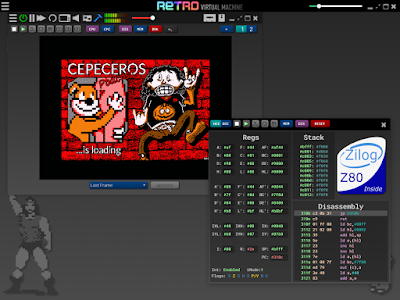

Retro Virtual Machine ejecutando un spam nada sutil XD

¿Oyes la llamada del ensamblador? ¿Veremos algún día un nuevo juego de David Perry para el Amstrad CPC?

Es gracioso que hoy, que estaba trabajando fuera (es sábado) me he visto instalando y aprendiendo Python. ¿Porqué? ¡Por que hecho mucho de menos programar! Cuando me jubile puedes estar seguro de que estaré haciendo juegos de nuevo.

Me encanta cuanto adoras al CPC. ¡Es gente como tu la que mantiene la memoria viva!

También soy mecenas de Retro Virtual Machine en Patreon. Espero poder desarrollar ahí algún día.

¿Quién sabe?

Una última pero muy importante pregunta: ¿cuantas veces ganaste el premio al programador más guapo? *risas*

¡Nunca! ¡Era el más alto!

Muchísimas gracias por tu tiempo. ¿Hay algo que te gustaría añadir para nuestros lectores?

¡Gracias por mantener vivo al CPC!

Muchas gracias a David Perry por su amabilidad.

ENGLISH

First of all, we would like to thank you for spending some of your scarce time with us. Let's start from the beginning: When did your interest in technology start? Which was your first owned machine?

I got interested at school in the early 1980’s, but my teachers wouldn't let me into the computer room, they said I was too young. When I was old enough they let me play with a ZX81, so that's the first machine. My mother bought me a used one from a girl at school who didn't want it anymore. Suddenly I could play (and make) games at home!

We all remember the deep impact that caused those very first games in our young retines. I am talking, of course, about those big machines with shiny lights and electronic sound called arcades. What were your favourite games as a kid?

The first video game I played was Pong, a friend had one for his TV. There was an arcade near my school, they had Pacman and Bump’n’Jump. The university by us had Donkey Kong 2, Missile Command and Phoenix. The Belfast Airport had the Star Wars sit-down arcade cockpit edition, and Dragon’s Lair. Overall that was a good set of machines to play! I probably did the best at Phoenix. I’ve always loved vertical shooters, another favorite is Moon Cresta.

At a certain point you decide to move to the “other side” and not only enjoy gaming but actually producing your own games. What moved you to take that step?

In the early 1980’s magazines were popular, there were lots of them focused on video games. You could lay out the magazine and type in the game code and play new games anytime you liked. All that typing made you learn how to type fast! It also taught you how to program games. “LET LIVES=3” is easy to understand, and cheat!

So I started modifying games until I could make my own.

How easy was it for you to access programming resources? Back in the early eighties, we could say that the access to Internet was really rare *laughs* Where did you find those resources? Which ones were your favourite?

The most important thing to me was getting books on programming. There was someone called Ian Logan (that I never met), who wrote some incredible books. Another was Toni Baker. They helped me SOOO much! I would have paid 10 times more for those books! (I still have them all.)

How important was this early access to programming resources in your future career? I mean, you spend most of your life doing games, so we all assume that it caused a deep impact on you. But, what did you learn in these first days that it proved useful after? Any interesting programming tricks that saved you time years later in more powerful machines?

At one point I decided to write a program that would work out how fast a program would run. It seemed like a good idea to me as I would be able to make my code faster. What was interesting was it made me look at every single instruction, and think about speed, and I could experiment with code until I found the fastest way to do something. I remember experimenting with self-modifying code, where the code would re-program itself when running. Fun!

You started your career very early publishing some listings on magazines for ZX80/81 and then jumped into the new shining Sinclair Toy, The ZX Spectrum. With it, you achieved your first milestones working with Mikro-Gen, where you published titles like Three Weeks in Paradise. But, at a certain point, you discovered a great competitor for the Sinclair computers called Amstrad CPC. How did you find the machine when you first heard of it? What moved you to learn programming for it?

Probably the first game I really got to work on that was “professional” was Pyjamarama. It was written by Chris Hinsley on the Spectrum, and we needed an Amstrad CPC version. So I made that version and it meant my first review was 10/10. I loved the Amstrad and made more games on it, but I also worked on the Spectrum and Commodore 64. I guess I wanted to learn them all!

Was it difficult to adapt to the new machine? We know both Spectrum and CPC share some components, but for example the video work it's quite different, being really easy to do a crappy job if you copy the way of working with the Spectrum on the Amstrad. What advantages did you find on the Amstrad CPC? Which are, in your opinion, its best features?

The Amstrad was different to the Spectrum, but at least the core programming language was the same. I found myself running out of memory, so I’d hide things on the screen that was not being displayed by the monitor. Lots and lots of tricks to get it to do everything needed. What was funny was we didn’t have a development kit, so we hacked together a way to download via the joystick port. Imagine code was virtually wiggling the joystick to download the games. It worked!

There's some contradictory information on the Internet and we would like to clarify. What can you tell us about your earlier jobs with the machine? Which games did you program for the Amstrad CPC before Great Gurianos?

Yes, Pyjamarama on CPC was my first. Great Gurianos was when I left Mikro-Gen and thought I’d start my own company. Elite offered me that game and sent me an arcade machine. (By the time it arrived I’d already made the game.)

If I may ask: In which Mikro-Gen games for the Amstrad CPC did you work?

I think I made Pyjamarama, Stainless Steel, Herbert’s Dummy Run and Three Weeks in Paradise on Amstrad at Mikro-Gen. (Long time ago!)

Speaking about games before Great Gurianos, the word out there is that you started working on the port of Ikari Warriors, it was finished but never published, being instead published a version by David Shea. What can you tell us about this project? The game appears all the time on the Top Amstrad CPC Games of all time, but seeing your other works with the Amstrad one has to wonder if you could have done even better…

David Shea was a rockstar, he was a good friend and I was a huge fan of his. I did start work on Ikari Warriors, but quite honestly he was a better Artist/Programmer as in those days we tended to do the art as well. I’m certain his Ikari Warriors would have ended out better.

Both Ikari Warriors and Great Gurianos are games published by Elite Systems, a company which also published Beyond the Ice Palace. How was working for a Company like Elite? What kind of support did you receive? If you are free to talk: how was the paycheck?

Beyond the Ice Palace was when I decided to run my first “team” project. We divided up the work and made the game on multiple platforms. That wasn’t as easy as it sounds as we were all used to working alone.

After Elite you start working with Probe Software and produce two games very similar regarding huge Sprites and tons of particles moving on screen at the same time. We are talking, of course, about Trantor The Last Stormtrooper and Savage. What memories do you have about the creative process involved in developing both games? Any funny anecdotes?

I went to visit Probe Software and met Fergus McGovern there. He introduced me to Nick Bruty who was building Trantor for the Sinclair Spectrum. I was asked to work on the Amstrad CPC version, so I did that at home. Over time Nick and I decided to work together as a team, one programmer, one artist, it was a match made in heaven as it helped both our careers.

It's incredible how nicely move both games in a machine like the Amstrad CPC, (in)famous for his graphics abilities regarding scroll, big sprites and tons of elements on screen. You have a very good reputation as a Spectrum programmer, but it should be even better regarding your CPC Skills! How did you achieve that? Which programming tricks did you use?

The CPC really mattered to me, it was my first professional games device and there were games on there that made me want to try harder, like Sorcery.

With Dan Dare III and Teenage Hero Ninja Turtles you achieved what I call the “trademark David Perry”, games with a really smooth multidirectional scroll, smaller screen size maybe and tons of explosions and elements on screen. What can you tell us about these works? Which were the biggest challenges you found and how did you solve them? How were you able to achieve such a smooth scroll while having tons of explosions on screen?

Having made lots of games, Nick and I started to wonder what we could do to push the limits of the hardware. That’s when we just went crazy, like three-games-in-one (Savage) and a Spectrum game called Extreme that even used line-drawing to give the player robot legs. We started experimenting with everything, 3D, lots of parallax etc. We just loved what we were doing, this didn’t feel like work at all.

We made a game called Crazy Jet Racer, and Virgin wanted us to rename it to Dan Dare III. This was a good move and in reality I kept finding my career would move faster when I worked with license games. Which would you buy? “Jumpy Man” or “Mario”? The brands really matter.

1991 would be the last year you worked on our beloved machine, having the Amstrad CPC started to fade away in favour of better and more powerful machines. It was regardless a very productive year in your career, with another “Trademark David Perry” games like Extreme or Captain Planet, plus Paperboy 2 and Smash TV. The market had changed a lot since you started your career. What do you remember of these uncertain times?

Probe Software needed games, games, games… We were doing everything we could to keep up with the demand. I barely even remember working on Captain Planet, it was a blur. Paperboy 2 was interesting as I had to find a way to generate the maps using code as there wasn’t enough room to store them the old-fashioned way. Smash TV was fun, but I nearly killed myself trying to carry the arcade machine up a flight of stairs. Don’t do that, I could be dead now. Crushed on stairs by Smash TV.

Did you already start to recycle yourself learning programming for the new hot machines while working on these games? Did you learn anything in this process that was useful for the last games you were developing for the 8 bit machines or was the totally opposite? Which programming tricks did you learn in your 8 bit career that were so useful that you kept using them no matter in which machine you were working?

The trick was to keep an open mind. People would tell you what you can and can’t do, “These chip commands are undocumented, you can’t use them!!!” I did. All the time! I also had great friends like Zareh Johannes. I remember once working on some Amiga code, trying to scroll the screen at a smooth 60 frames a second. It would hiccup! He looked over my shoulder and pointed to a problem. I remember thinking “How on earth did he understand my code that fast?” So I’ve been really lucky to have people like that in my life. They inspire you to learn more and get better at what you do.

Is programming an Art that relies on inspiration once you have some grounds or is it more like a sport that with time and training you can really achieve anything?

If you love something, it’s not work. If you’re having fun, time flies by. I explain programming is like solving puzzles, you get the same thrill when you get something working. It’s the practice that matters. You need to invest thousands of hours, then the language becomes natural, you can literally think in code. People think programming is boring, but it’s really not, there’s a key moment when you realize you can build just about anything you can imagine. That’s pretty awesome.

Apart from Ikari Warriors, are there more unreleased 8 Bit David Perry games that we should be looking for desperately? Do you still have your developing discs from back in the day? Is there a mythical place where your source code lives happily?

I did spend some time finding a lot of my old games that only appeared in magazines or books. Someone had typed them in so I was able to get the code. The games are written in basic, an example is Drak-Maze.

Here’s a game from 1983 written for a magazine in BASIC!

https://spectrumcomputing.co.uk/playonline.php?eml=1&downid=76613&__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=pmd_c3b51544ae81cb3ea63f67b9f133a5c2d0a305ab-1627796176-0-gqNtZGzNAjijcnBszQiO

Which tools did you use in your Amstrad CPC productions? Did you have enough with out-of-the-box software from back in the day or did you prefer to develop your own tools? If the answer is yes: are they preserved? They belong to a Museum!

I wish we still had that original joystick wiggler for the CPC. What’s interesting is my main development platform became the Amstrad PCW8512 (I didn’t have a PC), I used that to make games like Gurianos on.

Towards the end of the Spectrum, I used something called PDS.

https://retro-hardware.com/2019/05/29/programmers-development-system-pds-by-andy-glaister/

We have talked a lot about programming and developing, but how about the creative process of designing a game? Were you happy developing your own ideas or it was just easier to work on ports to the Z80 Machines of games of other developers? How was back in the day the way you had an idea since it was finally portrayed on a finished product?

When I made Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles with Nick Bruty, it went straight to #1 in the charts. Again it became clear that licensing brands is a good idea! When you have a #1 hit, it’s easy to get more work. :)

That said, Nick and I always had personal products, like Supremacy on the Amiga/Atari ST. Extreme, Crazy Jet Racer (Dan Dare III), Savage etc.

What did the Amstrad CPC mean in your career? Did it help you achieve your actual status in your career? How big is the place for it in your heart?

It was just such an incredible device for the time, I still can’t believe it came with a MONITOR and a full high quality keyboard. It was a very very important part of my career and my only regret is I never met Alan Sugar. I did meet Sir Clive Sinclair which was fun.

I also bought the Spectrum Next and can’t wait to play with it.

Are you up to date with the Amstrad CPC Scene? What are your favourite new releases from the last few years?

As I now live in the USA, sadly there’s not enough people aware of the CPC. What new games would you recommend I check out. I have an CPC emulator on Raspberry Pi and that’s how it lives on forever! I’m a big fan/supporter of emulation as it’s preserving the history of the industry.

Do you hear the call of the assembler? Will we see a new David Perry game for the Amstrad CPC someday?

It’s funny I was working away today (a Saturday) and found myself installing and learning Python. Why? Because I miss programming so bad! When I retire you can be certain I will be making games again.

I love how much you love the CPC, it’s people like you that will keep the memory alive!

I’m also a supporter of the Retro Virtual Machine on Patreon. I hope to develop on there someday.

A last but very important question: How many times did you win the “most handsome programer” award? *laughs*

Never! I was the tallest!

Thank you so much for your time. Is there anything that you would like to add for our readers?

Thanks for keeping the CPC alive!

A very big THANK YOU to David Perry for this interview.