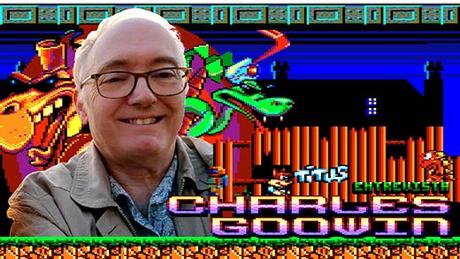

Mientras los medios de comunicación se centraban en chavales imberbes que supuestamente ganaban millones, una legión de desarrolladores hacían trabajos extraordinarios alejados de los focos. Hoy conoceremos un poco más la trayectoria de un artesano del píxel y el byte que estuvo implicado en proyectos durante toda la etapa comercial de los 8 bits. Con ustedes: Charles Goodwin.

ENGLISH INTERVIEW AFTER THE SPANISH TRANSLATION.

Muchas gracias por aceptar esta entrevista. Es todo un honor poder hablar con un desarrollador que estuvo ahí durante toda la locura de los ordenadores de 8 bits. Empecemos por el principio: ¿Cuándo y cómo empieza su interés en la tecnología?

Me estuve resistiendo durante mucho tiempo. En la escuela teníamos un teletipo conectado en algún sitio con un mainframe que ejecutaba programas muy básicos. Nada inspirador. En la universidad tomé un curso de computación que encontré muy aburrido. Luego empecé a trabajar para la STC (Standard Telephones and Cables) en 1980 (creo) y ahí hice un curso de código máquina en 8080, programando a base de switches siendo la salida una fila de leds que parpadeaban. De nuevo era nada inspirador. Sin embargo, en STC pudimos jugar a Colossal Cave y a un juego de Star Trek en el mainframe de la empresa, y mi compañero de piso (Graham Asher, conocido por el juego Valhalla para Legend) tenía un Sinclair ZX80. Así que imprimimos en papel el código del juego de Star Trek e intentamos teclearlo en el ZX80... Después de un rato aprendimos sobre las limitaciones de memoria de un pequeño ordenador doméstico comparado con un mainframe.

No obstante, eso despertó mi interés. Decidí escribir scripts que convirtieran los datos de un formato a otro, ya que estábamos moviendo la base de datos del mainframe a un nuevo mini-ordenador. Y entonces conseguimos un micro-ordenador, que era —y tenía la misma pinta que— este: Intertec Superbrain.

Escribí un juego muy simple usando BASIC —un juego que había visto en el Commodore Pet de un amigo— y lo copié a base de jugarlo —lo he hice ingeniería inversa, como dicen hoy en día—. El juego incluía una bola volando alrededor de la pantalla, siendo desviada para evitar que se chocara con obstáculos por tanto tiempo como fuera posible. También intenté escribir un programa de crucigramas para esta máquina —que creo que tenía 27K de memoria disponible— y descubrí sus limitaciones rápidamente. No obstante, a estas alturas estaba completamente enganchado y en algún momento me compré un Spectrum y aprendí a programarlo en ensamblador de Z80.

El Superbrain en toda su gloria. Fuente: Wikimedia

Si no estoy equivocado, también trabajabas desde joven con ordenadores tipo mainframes. ¿Cómo aprendió a programar esas bestias? ¿Qué lenguajes de programación usaba por entonces?

No programé mucho en mainframes, pero todo lo que recuerdo del mainframe de STC era que podía ejecutar BASIC, también JCL (Job Control Languaje) y el lenguaje de scripts que usé para convertir los datos, que se llamaba Easywork (!).

¿Cuan difícil fue adaptarse a esos microordenadores tan limitados? ¿De qué recursos disponía para aprender a programarlos? ¿Cuáles eran sus favoritos?

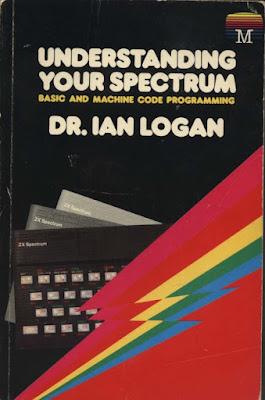

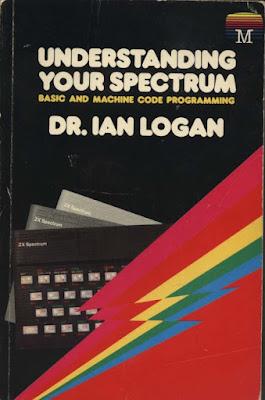

En ese momento escribir en ensamblador en un Spectrum con (creo) alrededor de 43K de memoria disponible no parecía tan limitado. Más limitadas estaban sus prestaciones sonoras. El chip de sonido del Commodore 64 fue un gran alivio cuando me puse con ellos. Estoy convencido de que tuve algún tipo de manual del Ensamblador. Estoy muy seguro de que tuve una copia de Understanding your Spectrum: Basic and Machine Code Programming, y posiblemente tuve también una copia de Spectrum Machine Language for the Absolute Beginner.

Un clásico atemporal

¿Qué le motivó a crear sus propios juegos? Para la mayoría de nosotros ya era suficiente jugar :-)

Posiblemente la misma necesidad que me llevó a pintar y dibujar, escribir mis propias novelas y crear mis propios cucigramas —sin mencionar a ser un master de Dungeons & Dragons—: Algún tipo de necesidad creativa...

Normalmente solemos ver que los desarrolladores suelen estar muy influenciados en sus primeras creaciones por los juegos a los que solían jugar. ¿Cuales eran sus favoritos?

Buah. A ver si me acuerdo... Creo que pasé un montonazo de tiempo jugando a Space Invaders cuando salió, además de algunos juegos de aventura. Había una recreativa en concreto que me gustaba y que permitía juntar a cuatro jugadores en una aventura de estilo D&D [Nota: se refiere a Gauntlet]. También Knight Lore y todos esos juegos de Ultimate.

La mítica recreativa de Gauntlet de la peluquería de Bobby

En algún punto se da usted cuenta de que es lo suficientemente bueno como para vender sus juegos. ¿Cómo fueron sus primeras creaciones como desarrollador de 8 bits? ¿Cuándo se dio cuenta que estaba listo para hacer también juegos?

Mi primer juego de Spectrum tenía algo que ver con manejar pegotes por ahí. He olvidado los detalles. El código era bastante lioso y solo fui capaz de hacerlo funcionar gracias al descubrimiento fortuito del juego de registros alternativos del Z80. No obstante no era vendible. El primer juego que vendí se llamaba Infernal Combustion y lo intenté vender por mis medios pero entonces a mi mujer se le ocurrió la brillante idea de ofrecérselo a Automata bajo el nombre Piromania, nombre que encajaba en su serie "Piman". Por cierto, creo que fui yo él que hizo la portada.

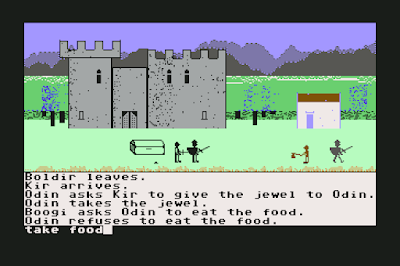

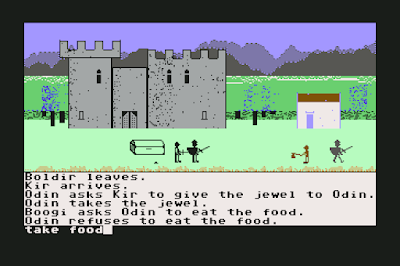

El primer juego que tiene acreditado es Valhalla, una interesante aventura que llegó al número 1 en ventas. ¿Cual fue su papel en este desarrollo? ¿Qué recuerda de él? ¿Estuvo involucrado en su conversión a C64?

Tal cual; estuve involucrado en su conversión a C64, no en el desarrollo original en el Spectrum, el cual corrió mayormente a cargo de Graham Asher —quien fuera mi compañero de piso durante una temporada y que también trabajó en STC—.

Version C64 de Valhalla

Valhalla tuvo una gran acogida en el mercado. ¿Llegó a pensar en dejar su trabajo y centrarse en hacer sólo juegos? ¿Era la paga suficientemente alta como para tentarle?

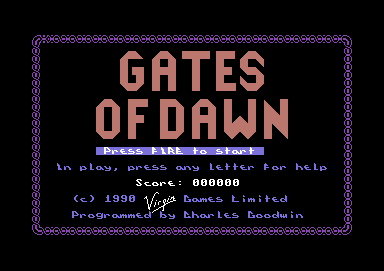

Lo hice. Me tomé una excedencia en STC en 1984 (creo) y conseguí un trabajo en Virgin Games. Ya les había vendido previamente un juego para el C64 llamado Gates of Dawn y otro para el Spectrum llamado Strangeloop, así que ya tenían mi currículo. Allí trabajé en Shogun y Dan Dare.

¿Cómo era tu equipo de desarrollo por entonces?

¿Te refieres a cuando estaba portando Valhalla? Supongo que un C64, una TV y algunos periféricos. Nada especial.

Tras Valhalla usted empieza a trabajar a un nivel completamente diferente entrando en Virgin y el Gang of Five, quienes eran ya posiblemente más de cinco personas a esas alturas :) ¿Qué tal era trabajar allí? ¿Era un freelance o tenías que ir a la oficina? ¿Qué tal era el ambiente de trabajo?

Era parte del GoF, trabajo en la oficina —¿en Bayswater?; no estoy seguro—. Así que tenía una mesa y la típica parafernalia. Creo que ya estaba trabajando en el CPC464 por entonces. El ambiente de trabajo estaba bien mientras los programadores estuvimos compartiendo una habitación, pero se volvió mucho peor cuando nos mandaron a una oficina separada con despachos compartidos con otros departamentos en cubículos. A esas alturas se podía oír al equipo de marketing hablando por teléfono constantemente, lo que hizo imposible mantener la concentración. Al final me fui y me uní a Softek / The Edge, que al final fue salir del fuego para caer en las brasas.

Pantalla de carga de Strangeloop

Virgin Games era parte de un enorme conglomerado empresarial propiedad del mediático Richard Branson. Compartía oficinas con otras partes del conglomerado como Virgin Music, quienes estaban produciendo discos para algunos de los artistas musicales más populares del momento. Seguro que debe tener un montón de anécdotas de sus visitas a la oficina :-)

Me temo que nunca llegamos a conocer a Richard Branson o a ninguna estrella musical.

¿Qué nos puede contar sobre Strangeloop? ¿Fue el primer juego que hizo en solitario? ¿Cuáles fueron sus fuentes de inspiración? ¿Cómo decidió el gameplay, el diseño de niveles, etc.?

Hmmm... no estoy seguro de como decidí todo eso, pero recuerdo que tuve la genial idea de generar el escenario, peligros, etc, usando un generador de números pseudoaleatorio, que me permitía tener un número enorme de pantallas, a las que entonces añadía detalles específicos.

Llegó incluso a tomar ese nombre para crear su propia empresa y publicar por sus medios Infernal Combustion. ¿Qué le llevó en esa dirección? ¿Tal vez pensó que podría prescindir de intermediarios y cobrar enteros los royalties si publicaba directamente su juego?

No estoy seguro del orden de los eventos. Creo que la compañía Strangeloop vino antes que el juego, así que posiblemente intenté primero la autopublicación. ¿Quizás porqué un montón de gente estaba haciendo lo mismo?

Pantalla de carga de Piromania

¿Por qué se publicó después como Piromania?

Lo que comentaba más arriba. Además sospecho que mi mujer y yo pensamos que Automata tenía mejor marketing.

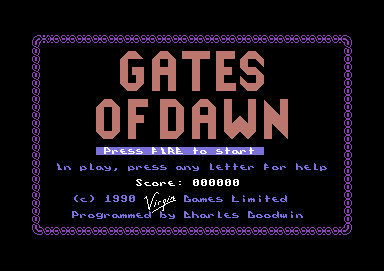

Usted vuelve de nuevo al C64 con Gates of Dawn para Virgin Games. ¿Qué recuerda de este desarrollo?

Me temo que no mucho. Los sprites y el sonido del C64 hicieron más sencilla parte de la programación. No es tan sencillo trabajar con el procesador 6502 como con el Z80, pero tenía sus puntos fuertes como las macros de lenguaje ensamblador y la Zero Page.

¿Por qué no lo convirtió al ZX Spectrum? Ya tenía experiencia con esa máquina...

¡No me acuerdo! Posiblemente porque por entonces prefería hacer cosas nuevas a convertir. Además, replicar el comportamiento de los sprites del C64 en el Spectrum no parecía ser muy divertido de hacer.

Gates of Dawn para C64

Strangeloop vino al Amstrad CPC e incluso fue extendido en Strangeloop Plus. Ese movimiento ya lo habíamos visto en otros éxitos de Virgin como Sorcery. ¿Sabe el motivo? ¿Era más rápido de hacer que un nuevo juego pero al extender el contenido servía de excusa para vender el juego de nuevo?

No creo que yo tuviera nada que ver en esa decisión, que yo recuerde. Pero tu análisis me suena muy posible.

Hablando del CPC: usted empieza a trabajar con el alrededor de finales de 1985 o comienzos de 1986. ¿Qué le llevó a probar una nueva plataforma? ¿Qué experiencia previa tenía con el CPC antes de desarrollar para él?

No tenía ninguna experiencia previa. Mis razones para cambiar al CPC serían que era una máquina mucho más agradable para trabajar, con mejores gráficos y sonido, y varias cosas integradas que con el Spectrum/C64 tenías que comprar aparte; además de mi procesador favorito junto a memoria dividida en bancos, que se podía aumentar a 128k si recuerdo correctamente.

¿Cómo fue adaptarse a esa máquina? Sí, comparte el Z80 con el Spectrum, pero tenía un sistema de vídeo diferente y ese diabólico chip CRTC que tantos dolores de cabeza le dio a muchos programadores.

No recuerdo haber usado el CRTC. ¿Tal vez siempre usé el tamaño de pantalla completo?

Shogun para Amstrad CPC

¿Tuvo ayuda de Virgin para esta adaptación?

Lo siento. No lo recuerdo.

Shogun es posiblemente uno de los juegos más complejos en los que usted ha trabajado. ¿Qué nos puede contar de este desarrollo? ¿Cómo le vinieron esas ideas? ¿Qué dificultad encontró en implementarlas?

Hasta donde yo recuerdo, el juego fue diseñado por Simon Birrell. Mi parte era principalmente los gráficos, a los que intenté darle una apariencia japonesa ya que había estado en una exhibición de arte de dicho país. Todavía conservo el catálogo de esa exposición, al contrario que los libros de programación del Spectrum.

¿Sentía alguna presión de Virgin a estas alturas? Pagaron dinero por la licencia del libro y produjeron una maravillosa edición en un estuche enorme de plástico, así que debieron invertir una buena cantidad de dinero. ¿No temían que un juego tan complejo no fuera del gusto para todo el mundo?

No sé. Simon supervisaría más tarde un intento de producir un juego para Palace que incluía clips de vídeo y cosas por el estilo, así que a él siempre le gustaron esas cosas.

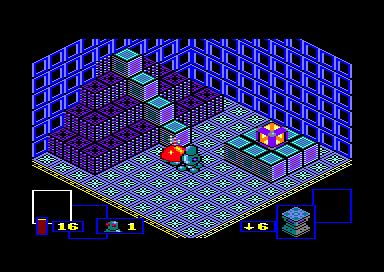

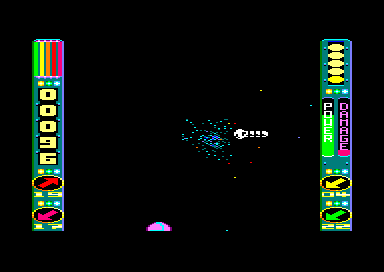

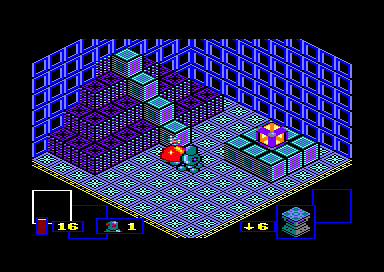

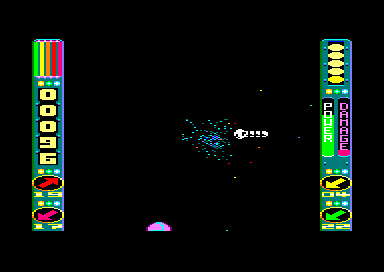

Palitron en acción

Tras Shogun usted hace dos juegos isométricos de Amstrad para The Edge: Palitron y Warlock. ¿Qué encontró tan atractivo en la perspectiva isométrica como para decidir hacer algunos juegos con ella?

Para empezar, el reto tecnológico. No obstante, es una forma de producir juegos con gráficos tridimensionales sin entrar en todas las complejidades de perspectiva, etc, así que es lo mejor de ambos mundos. Hacer juegos en auténtico 3D sin la ayuda de GPUs modernas es todo un desafío.

¿Cuales fueron los mayores desafíos al hacer ambos juegos comparado con sus juegos previos?

Supongo que dibujar el mapeado 3D y, en partícular, averiguar exactamente donde deberían estar los sprites en relación con él.

Si no estoy equivocado, se desarrollaron originalmente para el Amstrad CPC y luego convertidos a otros ordenadores. Si eso es cierto: ¿Qué encontró tan atractivo en el CPC como para hacer el juego para dicho ordenador y dejar que otros los convertieran?

Creo que esa decisión la tomo The Edge, en concreto Tim Langdell.

Otra pequeña maravilla isométrica llamada Warlock

¿Cuáles fueron sus inspiraciones para esos juegos? ¿Cómo decidió la jugabilidad, diseño de niveles, etc?

Imagino que la inspiración sería posiblemente Knight Lore, además de algunas recreativas.

¿Qué tal era trabajar en The Edge? Hemos oído algunas historias sobre lo que hoy en día es conocido como "crunch"...

No estoy seguro de si debería contestar a eso.

Después llegó By Fair Means, un juego con algo de controversia cuando Codemasters volvió a sacarlo a la venta con otro nombre, lo cual posiblemente afectó a las ventas. ¿Le informaron desde Codemasters de esta decisión? ¿Siguieron llegando los royalties?

Lo siento. ¡No lo recuerdo!

Una pequeña delicia pixelada

A estas alturas estaba claro que el mercado de los juegos de 8 bits se estaba reduciendo rápidamente. Curiosamente hizo sus mejores juegos a comienzos de los 90. Hablo de Swap para el C64 y de Prehistorik, Crazy Cars III y Titus The Fox para Amstrad CPC. Todos esos juegos fueron realizados para compañías francesas. ¿Cuál es la historia? ¿Cómo acabó trabajando para Mïcroids y Titus?

Bueno, la mayoría de esos juegos eran conversiones de PC, salvo Swap. Creo que acabé trabajando para ellos porque yo estaba en Palace y ellos compraron la compañía en algún momento.

Los juegos de Amstrad, en particular, fueron diseñados con una máquina de 16 bits como versión original y usted tuvo que convertirlos a una máquina más limitada como era el Amstrad CPC. ¿Cómo logró hacer un trabajo tan magnífico? No debió ser fácil recrear esos juegos en una máquina más limitada...

Creo que simplemente hice ingeniería inversa. No creo que tuviese acceso al código original, aunque ya había comenzado a programar para el PC en algún momento...

La simpática mascota de Titus en esta versión censurada

Usted ha mostrado una evolución durante su carrera como programador de 8 bits, pero con Titus The Fox alcanzó la cima. Incluso dominó las habilidades del CRTC para hacer scroll por hardware. ¿Cómo aprendió a hacerlo? ¿Tuvo alguna ayuda desde Titus?

Ahora es un poco confuso todo. No obstante, no creo que tuviera ayuda desde Titus. Recuerdo que me di cuenta que la manera más rápida de poner datos en pantalla era tratarlos como una pila y usar la instrucción push para transferir 16 bits a la vez. Creo que es la única forma de hacer eso con el Z80. Eso fue posiblemente para Crazy Cars, para pintar la carretera durante una interrupción.

¿Qué aprendió durante este periodo de su vida que le haya ayudado a lo largo de toda su carrera? ¿Algún truco de programación que fuera tan útil que lo sigue usando hoy en día?

Hacer las cosas orientadas a objetos ayuda ciertamente. Los juegos son naturalmente orientados a objetos, en mi opinión, siendo cada sprite o enemigo o lo que sea autónomo, y teniendo una interfaz para el resto del mundo del juego.

¿Podía un programador como usted ganarse bien la vida haciendo juegos? ¿Hubiera sido suficiente cómo para dejar su trabajo y centrarse en ello?

Bueno, hice eso una temporada. Sin embargo, después fui a una compañía que hacía software para videoclubs, y después a Psion. No obstante fue hecho redundante en Psion y volví a hacer juegos una temporada en Palace.

Crazy Cars 3 para Amstrad CPC

¿Cómo evolucionó su equipo de trabajo durante esos años?

El hardware esa simplemente lo que fuese necesario. Yo siempre trabajé en la máquina objetivo, creo, sin compiladores cruzados ni nada por el estilo. Al menos hasta que trabajé en Gameloft en 2010-2011...

El software comenzó siendo un ensamblador bastante sencillo y sin duda se fue volviendo cada vez más sofisticado, pero no recuerdo los detalles.

Usted estuvo activo durante toda la época comercial de los 8 bits y trabajó para un montón de compañías diferentes. Si echa la vista atrás a esos años: ¿qué fue lo mejor de trabajar en este mercado? Por el contrario: ¿qué le habría hecho nunca trabajar ahí si lo hubiese sabido?

Lo mejor fue poder trabajar en proyectos en solitario o con equipos muy pequeños. Sobre lo que me hubiera hecho no volver a trabajar en ello... bueno, ¡las horas y la paga!

Tras trabajar tantos años para tantas empresas diferentes debe tener posiblemente montones de anécdotas. ¿Cuales son sus favoritas?

Me temo que no estoy tan seguro de tener anécdotas.

Otro título de Mr. Goodwin: Solar Empire

¿Podía uno predecir el mercado o las compañías simplemente tenían interés en seguir las tendencias?

Unos cuantos tenían ideas rompedoras pero la mayoría creo que seguían tendencias.

Usted ya era un joven adulto cuando empezó a publicar sus juegos. Los medios de comunicación estaban vendiendo historias de éxito sobre "wizkids" que ganaban millones desde sus dormitorios. ¿Cómo se sentía usted entonces?

Yo disfrutaba simplemente del desafío, principalmente. Me gusta resolver problemas y hacer mis cosas artísticas. De hecho la apariencia de los juegos era muy importante para mi.

¿Conserva todavía su viejo código/discos/hardware?

Tengo unos cuantos.

Trivia: ¿Qué tienen en común Peppa Pig y Charles Goodwin?

¿Pudo publicar todos sus juegos o se le quedó alguno en el tintero?

El primero que escribí para el Superbrain no llegó a publicarse, como tampoco el primero que hice para el Spectrum, aunque en realidad era más un ejercicio de aprendizaje. Aparte de esos, el único que nunca se ha publicado fue uno que hice para el PC junto a mi amigo Chris Strangroom, quien por desgracia fue asesinado mientras estaba de vacaciones en Budapest. No me sentí con ganas de seguir adelante después de eso, aunque ya estaba listo para publicar y algunas compañías ya habían mostrado algún interés, aunque no recuerdo cuales.

¿Qué hay de sus libros? Si no estoy equivocado, usted solía escribir sus propias historias de ciencia ficción. ¿Cuales fueron sus influencias? ¿Se pueden leer en algún sitio?

De hecho estoy pensando en poner una en SubStack. Todavía no lo he hecho porque todavía la estoy editando un poco, pero debería estar pronto aquí.

Respuesta: Mr. Goodwin ha trabajado en el software usado para animar la serie

¿Oye la llamada del ensamblador? ¿Veremos algún día otra producción de Charles Goodwin para alguna máquina clásica?

Lo usé en mi ultimo trabajo en CelAction - siendo de x86, después x64, también MMX, SSE2 y AVX2. No obstante, ahora estoy (semi) jubilado, así que no se que será lo próximo que haga.

Permítame nuevamente darle las gracias por su paciencia y su amabilidad. ¿Hay algo que le gustaría añadir para nuestros lectores?

Muchas gracias. Es un honor para mi que haya quien recuerde estas cosas del pasado, y siento si no tengo muchas anécdotas. Si recuerdo algo más, os lo contaré.

ENGLISH INTERVIEW

Thank you so much for accepting this interview. It's a total honour for us to be able to talk to a developer who was there during the whole 8-bit computer madness that took Europe by storm. Let's start from the beginning: How and when started your interest in technology?

I resisted for a long time. At school we had a teletype linked to a mainframe somewhere, which ran very basic programmes - hardly inspiring - and at university I did a computing course that I found very boring. I started working for STC (Standard Telephones and Cables) in 1980 (I think) and there I did a course in using machine code on an 8080 - programming it by setting switches, the output being a row of flashing LEDs. Which again was less than inspiring. However, also at STC, we got to play “Colossal Cave” and a “Star Trek” game on the company mainframe, and my flatmate (Graham Asher, of Legend / “Valhalla” fame) had a Sinclair ZX80. So we got a printout of the Star Trek game’s code and tried typing it in… After a while we learned about the memory limitations of a small home computer vs a mainframe.

However, my interest was piqued. I somehow decided to write scripts that would convert data from one format to another, because we were moving the mainframe’s database to a new mini-computer. And then we got a micro-computer, which was - and looked exactly like - this: Intertec Superbrain

I wrote a fairly simple game on this using BASIC - the game I’d seen on a friend’s Commodore Pet, and I copied it from the gameplay (or “reverse engineered” as we’d say nowadays). This involved a ball flying around the screen being deflected to keep it from running into obstacles for as long as possible. I also attempted to write a crossword grid-filling programme on this machine (which I think had about 27k of available RAM) and discovered the limitations of it quite quickly. However by this point I was hooked, and at some point bought a Sinclair Spectrum, which I taught myself to programme in Z80 assembly language.

The Superbrain in all its glory. Source: Wikimedia

If I am not mistaken, you were already working from a young age with mainframes. How did you learn to code for those beasts? Which programming languages were you using back then?

I didn’t do a lot of mainframe programming, but all I remember about the STC mainframe was that it would run BASIC, also JCL (Job Control Language) and the script language I used to convert data, which was called Easywork (!)

How difficult was it for you to adapt to those very limited microcomputers? What resources did you have to learn how to code? Which ones were your favorites?

Writing in assembler on a Spectrum with (I think) around 43k of available memory did not seem limited at the time. More limited were the sound capabilities (the Commodore 64’s sound chip came as a great relief when I got onto those). I’m sure I had some sort of assembly language manual - I’m pretty sure I had a copy of Understanding your Spectrum: Basic and Machine Code Programming and possible Spectrum Machine Language for the Absolute Beginner.

A truly classic

What moved you to try to create your own games? For the most of us, just playing them was enough 🙂

Probably the same urge that led me to paint and draw, write my own novels and produce my own crosswords (not to mention being a Dungeon Master in Dungeons & Dragons). Some sort of creative urge…

We usually find that game developers are heavily influenced in their first creations by the games they were playing. Which one were your favorites?

Oh boy… trying to remember… I think I spent an awful lot of time with Space Invaders when it first appeared, plus various adventure games, and there was one particular arcade machine I was keen on that involved four players in a D&D-type adventure. Also Knight Lore and all those Ultimate ones.

The legendary Gautlet cabinet at Bobby´s hairdressing salon in Copenhagen.

At a certain point you think that you are good enough to try and sell your games. How were your first creations as an 8 bit developer? When did you realize that you were ready to make games as well?

My first Spectrum game was something to do with steering blobs around - I forget the details - the code was fairly spaghettified and I only made it work thanks to the fortuitous discovery of the alternate register set on the Z80. However it wasn’t saleable. The first game I sold was called “Infernal Combustion” which I tried to sell off my own bat but then my wife had the bright idea of offering it to Automata with the name “Piromania” - which fitted in with their “Piman” series. (I think I drew the cover picture, by the way.)

The first game credited to you is Valhalla, a very nice adventure who went number 1 in sales. What was your role in this development? What do you remember about this? Were you involved in its porting to C64?

Exactly that, I was involved in porting Valhalla to the C64, not the original development on the Spectrum, which was largely down to Graham Asher (who was my flatmate for a while, and who also worked at STC).

Valhalla, C64 version

Valhalla had a great market reception. Did you ever think about quitting your regular serious job and focusing on just doing games? Was the pay enough to tempt you?

I did. I took voluntary redundancy from STC in 1984 (I think) and got a job with Virgin games. I’d already sold them a game for the C64 called Gates of Dawn, and one for the Spectrum called Strangeloop so they had my CV, as it were. I worked on “Shogun” and “Dan Dare”.

What was your coding setup then?

You mean when I was porting Valhalla? I guess a C64, TV, and peripherals. Nothing fancy.

After Valhalla you start working at another complete level with Virgin and the Gang of Five, which probably were already more than 5 people at that time :) How was working for them? Were you a freelancer or did you have to go to the office? How was the working environment?

I was part of the GOF, working in the office (in Bayswater??? Not sure now). So I had a desk and the usual stuff, I think I was on the CPC464 by then. The working environment was fine while the programmers were sharing a room but got a lot worse when we were moved into separate offices with a shared roof space, so to speak (so effectively the walls were like partitions, with no roof). At that point we could hear the marketing people on the phone constantly, which made concentration impossible. Eventually I left and joined Softek / The Edge, which turned out to be a frying pan-to-fire sort of move.

Loading screen for Strangeloop

Virgin games was a part of a huge media company owned by the mediatic Richard Branson. It shared office space with other parts of the conglomerate like Virgin Music, who produced albums for some of the most popular music stars. I am sure you should have tons of anecdotes in your visits to the office 😀

I’m afraid we never got to meet either Branson or any of those music stars…

What can you tell us about Strangeloop? Was it the first game that you did alone? What were your inspirations? How did you decide gameplay, design, etc?

Hm… not sure how I decided all those things but I do remember that I had the bright idea of generating the landscape, hazards etc using a pseudo-random-number generator, which enabled me to have a huge number of rooms, to which I then added a few specific things.

You even took that name to make your own company and publish yourself Infernal Combustion. What moved you in this direction? Maybe you thought you would probably cut the middleman and keep all of the royalties if you were able to directly publish your own games?

I’m not sure about the order of events. I think the company Strangeloop came before the game - so I probably tried to self-publish first, perhaps because lots of other people were doing similar things?

Pantalla de carga de Piromania

Why was it later published as Piromania?

See above. Plus I suspect we (my wife and I) thought Automata had far more marketing ability.

You try again with Virgin Games with Gates of Dawn for the C64. What do you remember about this development?

Not much, I’m afraid. The C64 sprites and sound made some of the programming a lot easier. The 6502 processor isn’t quite as straightforward to work with as the Z80, but with assembly language macros and the zero page it has its own strengths.

Why didn't you port it to the ZX Spectrum? You already had experience with the machine…

I can’t remember! Probably because at the time I was keen on doing new things rather than porting. Plus trying to replicate the behaviour of the sprites on the C64 on the Spectrum wouldn’t have seemed like much fun.

Gates of Dawn for the C64

Strangeloop came to the Amstrad CPC and was even extended in Strangeloop Plus. That´s a move that we already saw Virgin make with some of his greatests hits like Sorcery. Do you know why? Was it quicker to do than a new game but extending the content was the excuse to sell the game again?

I don’t think I had anything to do with that, that I remember. But your analysis sounds quite likely to me.

Speaking about the Amstrad CPC, you start working with it around the end of 1985 or beginning of 1986. What moved you to try a new computer platform? What previous experience did you have with the CPC prior to developing for it?

I didn’t have experience prior to developing for it. My reason to move would be that it was a far nicer machine to work on, with far superior graphics and sound, various things built in that with the Spectrum/C64 had to be extras, plus my favourite processor (together with banked RAM, so it could be extended to 128k if I remember correctly).

How was adapting to program for that machine? Yes, it shares the Z80 with the Spectrum, but had a different video System and that diabolical CRTC chip that gave headaches to many programmers.

I don’t recall using the CRTC chip, so maybe I just worked with the available screen size?

Shogun for the Amstrad CPC

Did you have help in Virgin with this adaption?

Sorry, I can’t remember.

Shogun is probably one of the most complex games that you worked on. What can you tell us about the development of this game? How did you come to the ideas? How difficult was it to implement all of them?

As far as I recall this was designed by Simon Birrell. My side of it mainly involved the graphics, which I tried to give a Japanese appearance to - having been to an exhibition of Japanese art (I still have the catalogue, unlike those Spectrum books).

Did you have any pressure at this point in Virgin? They paid money for a book license and produced a gorgeous edition in a big plastic box, so they should have invested a good amount of money in the production of this one. Were they not worried that such a complex game could not be the cup of tea of everyone?

I don’t know. Simon later went on to oversee an attempt to produce a game for Palace which involved movie clips and suchlike, so he was clearly into that sort of thing.

Palitron in action

After Shogun you made two Amstrad isometric games for The Edge: Palitron and Warlock. What did you find so attractive from isometric games that you decided to do some?

To start with, the technical challenge. However it’s a way to produce three-dimensional games without going into all the complexities of perspective, etc, so kind of the best of both worlds. Producing genuine 3D games without modern stuff like GPUs is quite a challenge.

What were the biggest challenges to do both games compared to your previous ones?

I guess drawing the 3D landscape - and in particular, working out exactly where sprites were in relation to it.

If I am not mistaken, they were developed originally for the Amstrad CPC and later ported to other computers. If that's true: what did you find so attractive in the Amstrad CPC to do the game for it and let others port it to other computers?

I think that decision was made by the Edge, i.e. Tim Langdell.

Another small isometric wonder called Warlock

What were your inspirations for those games? How did you decide gameplay, level design, etc?

I imagine the inspiration was probably “Knight Lore” plus various arcade machines…

How was working for The Edge? We have heard some stories about what today is known as “crunch”...

I’m not sure I should answer that.

Then came By Fair Means, a game that had a bit of a controversy when Codemasters re-released it with another name, which probably harmed the sales. Were you informed by Codemasters? Did the royalties keep flowing?

Sorry, can’t remember!

Prehistorik for the Amstrad CPC

It was clear at this point that the market for the 8 bit machines was shrinking quickly. Funny enough, you did your best games at the beginning of the 90s. I am talking about Swap for the C64 and Prehistorik, Crazy Cars III and Titus The Fox for the Amstrad CPC. All those games were done for french companies. What's the story behind? How did you end up working for Mïcroids and Titus?

Well most of those were conversions of existing PC games (except for Swap). I think I ended up working for them because I was working for Palace, and they acquired Palace at some point.

The Amstrad games in particular were designed with a 16bit machine as the original version and you had to port it to a more limited machine as it was the Amstrad CPC. How did you do such great work? It wasn´t probably easy to recreate a game on a more limited machine…

I think this was all just reverse engineering. I don’t think I got to look at the original code - although I did start coding on the PC at some point…

The Titus mascot takes protagonism

You haven been showing an evolution along your career as an 8 bit programmer but with Titus The Fox you reached the top. You even dominated the hardware scrolling abilities of the CRTC chip. How did you learn to do that? Did any of Titus help you?

This is all a bit of a blur now. I don’t think I had any help from Titus, however. I do recall that I worked out that the fastest way to put data on the screen was to treat it as a stack and use the push instruction to transfer 16 bits at a time (I think the only way to do that with the Z80). That was probably for Crazy Cars, to draw the road during an interrupt.

What have you learned during this period of your life that helped you along your career? Any programming tricks that were so useful that you still use today?

Making things object-oriented certainly helps. Games are naturally OO, in my opinion, with each sprite or hazard or whatever being autonomous, and having an interface to the rest of the “game world”.

Could a programmer like you make a good living doing games? Would it have been enough to quit your day job and focus on it?

Well I did for a while, however I then moved to a company that wrote software for video lending shops (as we used to have back then), and then to Psion - however Psion made me redundant and I went back to games for a while at Palace.

Crazy Cars 3 for the Amstrad CPC

How did your coding setup (hardware, software) evolve during these years?

The hardware was just whatever was necessary - I was always working on the relevant machine, I think, not cross-compiling or anything. (At least until I worked for Gameloft in 2010-11…)

The software started as a pretty basic assembler and no doubt became more sophisticated, but I can’t remember details.

You have been there for the complete 8 bit commercial time and worked for a lot of different companies. If you look back at these years: what was the best of working in this market? On the contrary: what could have made you never work on it if you knew?

The best was being able to work on a project either solo or in a small team. What would make me never work on it - well, only the hours and pay!

After working so many years for so many different companies you probably have tons of anecdotes of those crazy years. Which ones are your favorites?

I’m not sure that I do have anecdotes, I’m afraid.

Another Mr. Goodwin game: Solar Empire

Could one predict which way would turn the market? Or the companies were mainly interested in following the trends?

A few people had groundbreaking ideas but mostly I think they followed trends.

You were a young adult when you started publishing your games. The media was selling success stories of “wizkids” earning millions from their bedrooms. How did you feel back then?

I just enjoyed the challenge, mainly. I like solving problems and also doing “arty” things. The actual appearance of the games was quite important to me.

Do you still keep some of your old code/discs/hardware?

I have a few.

Trivia: What does Peppa Pig and Mr. Goodwin have in common?

Were you able to publish all of your games or were there some that never saw the light?

The first one I wrote on the “Superbrain” didn’t get published, neither did the first one I wrote for the Spectrum, which was really just a learning exercise. Apart from that, the only one that wasn’t published was one I wrote for the PC with my friend Chris Stangroom, who was unfortunately murdered while on holiday in Budapest. I didn’t feel like pursuing it any further after that, even though it was ready to go and had had some interest from one of the games companies, I forget which one now.

How about your books? If I am not mistaken, you used to write your own science fiction stories. What were your influences? Could we read any of them nowadays somewhere?

Actually I’m thinking of putting one on SubStack. I haven’t actually done so yet, because I’m still editing it a bit, but it should be there soon. It will be on https://lizjr61.substack.com/ when it appears.

Answer: Mr. Goodwin worked on the software used to animate the serie

Do you hear the call of the assembler language? Will we see someday another Charles Goodwin production for the good old machines?

I used it in my last job for CelAction - that being x86, then more recently x64, also MMX, SSE2 and AVX2. However I’m now (semi) retired, so I’m not sure what I’ll be doing next.

Once again, thanks for your patience and your kindness. Is there anything that you would like to add for our readers?

Thank you very much. I feel honoured that anyone remembers these things from the past, and sorry that I don’t have a great fund of anecdotes. If anything comes back to me, I’ll add it.